“Well there are many ways of being held prisoner.” Anne Carson “Whacher”

I peel back the edge of her Welcome mat. The key is in the usual place. I let myself in. I am quiet. I’m always quiet. The night will be ruined if I wake her too soon. In the hall she’s left his clothes draped over the banister: striped pyjamas, a dressing gown, a pair of burgundy cord slippers. I heel my trainers off and slip out of my clothes. I keep my own underwear on. She has not insisted upon his underwear. There are certain things you can’t ask of a stranger, even if you’re paying him.

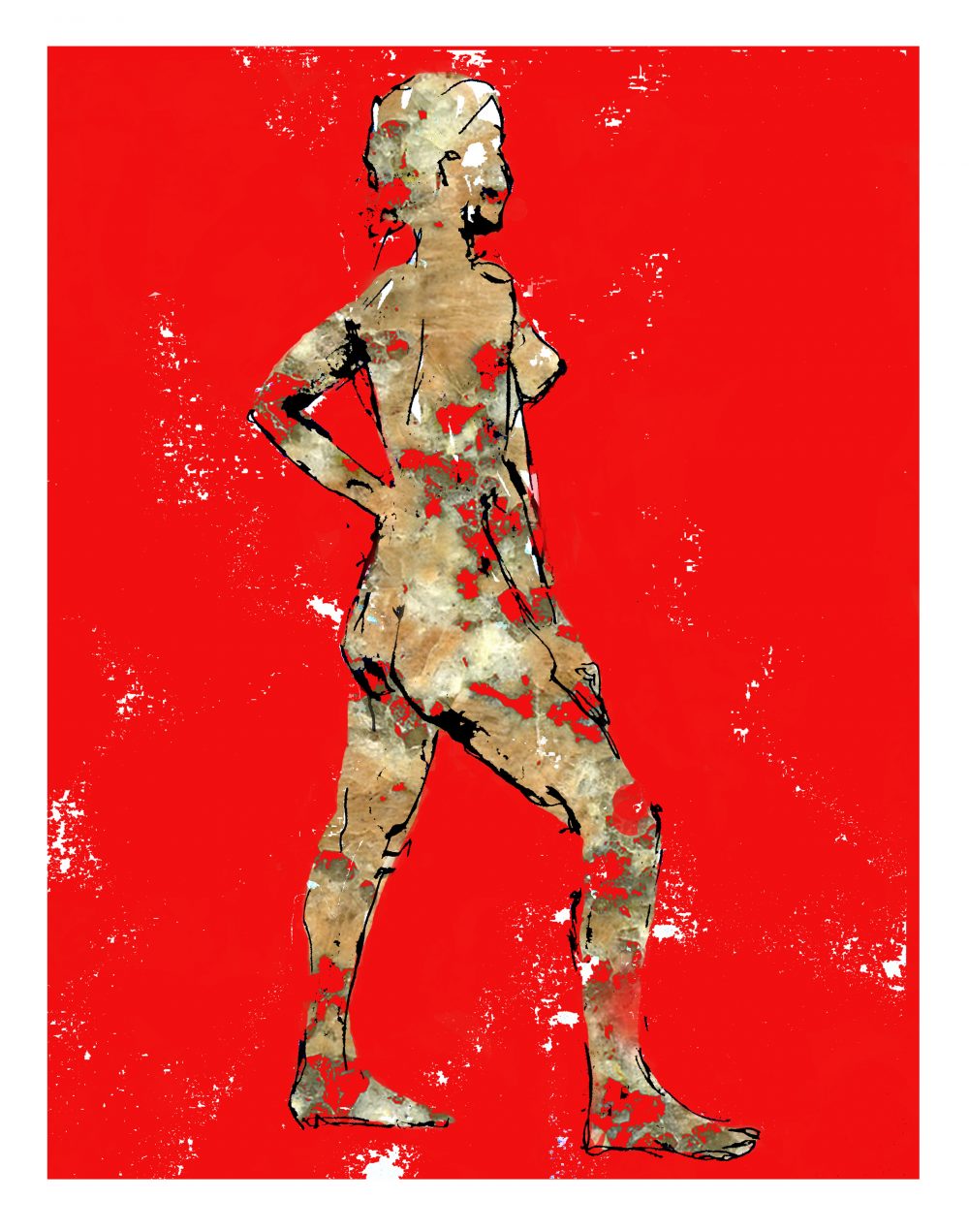

I hurry into his pyjamas. I don’t like the idea of standing, almost naked, in her hall. There’s nothing sexual about our arrangement. She’s been clear about this. I’ve had every opportunity, but I’ve never once overstepped the mark. It’s not because I’m a professional, though I do take my job seriously. I just don’t have the inclination. She’s still young and attractive enough: slim and delicate, with olive skin. Sometimes, I catch a glimpse of a breast or a slice of pale thigh peeking out from under the duvet and I think, “Jesus, Mikey what’s wrong with you?” Once, she fell asleep with her nightdress hoiked up round her waist and I could see everything. I didn’t know whether to cover her up. She might have considered this interference. She’d specifically asked me not to interfere. I felt, for the first time, voyeuristic; standing over her, with all her private thoughts exposed. Still, she did not move me then and, even now, several months in, there’s no lust in me when I lie next to her or perch on the bed’s edge watching her sleep.

She’s too sad. It’s a kind of ugliness. I couldn’t touch her, even if she asked me to.

There’s a distance, like glass, which sits between us.

I can’t get myself past the thought of him.

I shove my feet into his slippers and belt his dressing gown. His clothes fit perfectly. They always do. We’re exactly the same size. Mostly, I wear his pyjamas. Sometimes she leaves out jeans or tracksuit bottoms and a casual sweatshirt. Once, she wanted me in his suit. I didn’t know how to do the tie properly. I’d never learnt how to. My school had no real uniform, just sweatshirts with the school’s name embroidered on the chest. Ties would have been beyond the sort of boys who went to my school. I wore his tie looped loosely round my neck, the collar open and drawn back like a dishevelled businessman. I examined myself in the mirror above the mantelpiece. There wasn’t much light in the living room but I could still see that I looked smart, older too. The suit fitted snugly across the chest and shoulders. His clothes aren’t my style, but they always sit well on me.

She has my measurements: chest, waist, sleeve and inner leg. Her advertisement also asked for shoe size and a recent photograph. I sent her the one I’d had taken when I was thinking of doing my driving test. I’m sure she never expected to find such a good likeness. I’ve seen photos of him since. She has them framed all over the house: her and him, and some folks they’re clearly related to. We could easily be brothers. My eyes are bluer and he’s got better teeth, but a man on a galloping horse would be hard pressed to tell the two of us apart. She could probably have made do with somebody smaller, or even slightly larger, so long as they had his hair and colouring. With me she doesn’t have to compromise. I’m the living spit.

In her first email she said I was perfect. I remember the way she phrased it exactly, “I can’t believe how perfect you are.” No one had called me perfect before. She said it was almost painful to look at my photo; the resemblance was that striking. If I didn’t mind growing my hair out a bit and perhaps, not shaving before I came ‘round, then the job was mine. She’d pay me fifty quid per evening. Would this be enough? I said it would. Sure, all I’d be doing was standing about. She couldn’t tell me how long the job would last. “I’m not sure,” she said, “I’ve read so many books. They all say everybody grieves differently.”

I say, “she said,” but I’ve never actually heard her speak. All our correspondence has been via email. She insists upon distance and I’m happy to respect her wishes. Maybe, if we’d met early on it would’ve been ok. But now, after so many nights together, it’d feel weird to talk face to face. I wouldn’t know what to say to her. I’m sure she’d be disappointed in me. She’d realise I’m not the same as him. He was a smart bastard. I’ve seen the books in his study. You don’t have a study if you’re not smart. There are three different degrees, framed above his desk: one for English Literature, two for Law. I’d say he made his money from Law. Their house is the fanciest house I’ve ever been in. His name was Wilson. That’s a smart bastard name. Normal people don’t have second names for first. His surname was Greene. Not ordinary Green like the Greens who lived two down from us. Greene with a high and mighty, extra E.

Which makes her, Mrs Greene. I call her that in my head -the full whack of it, Mrs Greene- though I’d guess from looking at her, she’s not that much older than me. She doesn’t want me knowing her first name. It’s another way of ensuring our set up remains professional. She signs her emails Mrs Greene and, on Fridays, writes me a cheque from their joint bank account. She leaves it in a white envelope on the kitchen table: Mr W and Mrs L Greene. I have her down as a Laura. Her cheekbones are too high for a Louise. I’ve been round the house looking for something to confirm my suspicions. I’ve found nothing: not so much as a birthday card. There is more of him than her left here.

In my third email I asked what happened to her husband. I was polite about it, but I wanted to know. “Sorry to hear about your loss,” I wrote. “Was it sudden?” She said, “yes,” which could have meant cancer, a car accident or -in this part of the world- some kind of killing. People usually specify when it’s cancer or an accident, and he doesn’t seem like the sort to get himself shot. I assume it was suicide. We’ve a lot of suicide round here. There’s been three on our estate already this year; all fellas about my age. You’ll have seen it on the news. They always cite the same three reasons: depression, unemployment and something to do with being working class. Round our way, we’ve stopped saying, “he took his own life.” It sounds too soft. It rolls off the tongue like a kinder sentence. He took his mammy to the pictures. He took his own sweet time. We call it suicide. There’s strength to be found in giving a thing its proper name. Suicide’s a slippery word. It’s like spilt drink. It goes seeping into everything.

I bet if I pressed her, she’d say, “my husband took his own life.” You wouldn’t say suicide in a house like this. I’ve never asked for details, though I’d like to know which of their thirteen rooms he done it in.

I shove my own clothes into the hall cupboard. I don’t want to come upon my actual self later in the evening, when I’m fully into being him. I pad into the kitchen to put the kettle on. I’m supposed to make myself at home. I’m to wander round the house doing things he used to do. She emailed me a list of these activities. Things My Husband Does at Night. I was quick to note the tense she used: does not did. She’s not yet lost him in her head.

The list was unsurprising. He drinks whiskey from a special tumbler and tea in the mug with the Man United crest. He works late, spreading his papers across the kitchen table. He does not smoke. He keeps the TV on, locked onto one of the sports channels, with the sound set to mute. Occasionally he paces, up and down the hall or takes his fists to the punch bag which is hanging in the double garage. He rarely sleeps. He watches her sleep instead. When he does manage to get over, he lies on his right side facing the window. He wears pyjama bottoms and a vest in bed. Sometimes he showers late at night. He says this helps to clear his head. Sometimes he watches pornography on his laptop, just a half hour or so, and not the really heavy stuff. Sometimes he does this next to her in bed.

I have not yet done this, though the laptop’s there, and she’s given me the Internet password. She could easily have left porn off the list if she didn’t want me to. I’ve nothing against the idea in principle. Most men do it from time to time. I’ve a fondness for the Asian stuff myself. But it depresses me to see she’s noted porn, next to how he takes his tea.

I open the fridge in search of milk. He took his black, but I can’t stomach tea without a drop of milk. Her fridge is always pathetically empty. Skimmed milk’s in there, a bottle of salad dressing, something green and leafy, shoved into the bottom drawer. Occasionally she’ll have olives or the half-consumed remains of a take-away sandwich. Nothing more. I’ve no idea what she lives on. You can tell a lot about a person from the state of their fridge. Not to say that mine’s much better. Last time I checked I had a bottle of red sauce, two tins of Harp and a plastic tub of leftover sweet n’ sour. It’s not like it was when I lived with my mum. Her fridge was always stuffed to the gills.

The fridge light flicks on. I am anticipating three glass shelves of nothingness. Instead, I find all sorts of fancy breakfast foods illuminated in the glow. Eggs. Freshly squeezed orange juice. Croissants. Bacon. Cream cheese. Everything, even the eggs, are from Marks and Spencer’s. More money than sense, I think, though it’s heartening to see her appetite’s back. There is so much food, I wonder if she’s having somebody over for breakfast. I glance to the right, confirming my suspicions. There are two mugs set out on the breakfast bar, cutlery and napkins. I’ve been here every night for eight weeks now, and I’ve never seen evidence of anyone else. I close the door sharply, forgetting all about my milk.

I know she has family. They’re in the photos: a sister who looks like her -but younger- and parents, posed next to them on their wedding day. Where are they? I can tell from the unused hand soap in the downstairs loo that nobody comes to visit. Nobody calls either. She leaves her mobile charging on the kitchen counter. It sits there from eleven to eight and does not ring. The sofa is never sat upon. The whole place stinks of loneliness. Eventually it wears you down. You start wondering if it’s rubbing off on you.

I’ve taken to leaving it an hour or two before I go up to her room. I used to make a point of lying beside her as soon as I arrived. When you’ve just nodded over, your sleep’s not as thick as it gets later on. You’re more aware of the actual world. I thought she might be able to tell somebody was watching her. Now, I don’t go up ‘til after midnight. Any earlier and her cheeks are still damp from crying. She’ll have that puffy, sobbed-yourself-to-sleep look around the eyes. I don’t like seeing her like that. It’s just a job, I tell myself. Stop being so soft. You’re offering a service, Mikey. You’re actually helping her. Whatever way I spin it, I always leave feeling shit about myself.

Why did I get involved? The money was good. Of course, I was sympathetic too. I was all, “that must be really hard,” when she said she was lonely. I even told her I understood exactly what she was going through. Really, I thought she was a headcase. She’d probably got the idea from that film, Ghost; the one where Patrick Swayze does pottery. I didn’t even question her logic when she told me everything. “I don’t believe in ghosts myself,” she said. “I wish I did. The idea of having him come back to haunt me sounds really comforting right now. Obviously, that’s not going to happen. So, I was thinking maybe I could have the next best thing. I could find someone -somebody like you, Mikey- who looked a lot like my husband, and get them to dress up in his clothes and wander round the house, kind of haunting me. I don’t want you to try and scare me. It’s not about jumping out of cupboards or hiding under the bed or anything. I just want you to be present in the house. Act normal. Do the things he used to do. It’d be such a comfort to me.”

“Alright,” I said, “I can totally haunt you.” I was desperate for cash. I’d nothing coming in but the basic dole and the bills are mental when you’re living alone. I’ll be honest. I kind of despised her. Entitled, was the word that came to mind. Yes, it’s shit to lose your husband. But lots of folks are in a similar boat. Everybody’s a wee bit lonely. They said so on the telly. It’s an epidemic; three quarters of old folk feel isolated. Most people can’t afford to throw money at their loneliness. They have to make do with drink and religion, or they get a cat. Not her. She had money enough to hire me. Well, if she was that desperate, then I’d take her money. It wasn’t exactly taking advantage. In a way we were helping each other out.

I haven’t told anyone about my new job. Sure, who’s going to notice that I’m out every night? My mum’s the only person I talk to and I only see her once a week. Last week she asked if I’d any work on. I said, “I’ve a wee gig delivering pizza,” just in case she called late at night and wondered why I wasn’t in. I suppose this means I know our arrangement’s wrong. If I didn’t feel guilty, I wouldn’t lie.

I step back from the fridge. There’s a Post-It note stuck to the door. I peel it off and hold it up to my face. My name’s on it, so it’s meant for me. She’s asking me to stay for breakfast, if I’m not rushing on to something else. She’d appreciate having someone to talk to, even just for half an hour. “Ps,” she’s written at the bottom, “I’d pay you double for your time.”

I hold the yellow slip of paper in my hand. I read it three times top to bottom. She has a particular way of phrasing herself: polite and formal, like one of those ladies who reads the news. I picture her upstairs in the big Kingsize bed. The white laundry smell of their bedroom. Her perfectly manicured fingernails. The line of tears dried into her cheeks like snail tracks cutting through her powdery skin. Again, the tear tracks, and the crumpled tissues I sometimes find wadded up in her fists.

I know all the details of her by heart. I’ve spent so many hours just watching her sleep. Would it be any different if she wasn’t sleeping? If we sat opposite each other, drinking coffee and eating toast? Would it feel weird? I try to imagine us sat at the table with the morning light creeping under the blinds. I’d be back in my own clothes. I wouldn’t want her thinking me him. If I was me, that would be a new thing. I’d be Mikey and she’d be Laura, (or maybe Linda), and we’d be awkward together as folks are when they’ve never met. It’d be nice, I think, to have the company. I eat all my meals in front of the TV.

Maybe, breakfast would become part of our routine. We’d eat. We’d talk. We’d discover all the things we have in common such as loneliness and taking milk in our tea. Eventually, she’d feel a tiny bit better. She’d put make up on, and proper clothes and think about going back to work. She’d text her sister and this text would read, “it’s time I started moving on.” I follow this thought through to its natural conclusion. She’d wonder what she was thinking of, paying a stranger to walk around her house at night.

To Hell with that, I think. It doesn’t seem fair. Why should she be less miserable than me? I remind myself that this is a business arrangement. Emotions shouldn’t come into it. I take a biro out of the pot of pens she keeps on the counter. Under her message, I write, “sorry, I’ve got plans with my mates.” It’s a lie, of course. I don’t have any mates; nobody to knock around with at the weekend. Only Mum, and she doesn’t count. I picture her finding the note tomorrow morning. She’ll think I’m out playing five-aside or meeting the lads for a fry. She’ll feel lonelier then than she’s felt in weeks. She won’t risk asking again. Serves the posh bitch right, I think, and add a smiley-face emoji to the bottom of my note. This should make her feel really shite. I’m not like her: weak, pathetic, desperate for company. Maybe, I am, but nobody’s noticed yet. Surely, this means I’m stronger than her.