ONE

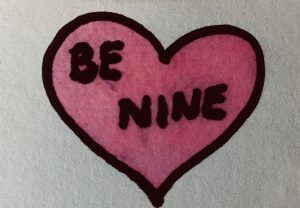

A child’s candy, a little circle pink as lamb’s blood, sweet and tasting of the goodness of maltodextrin and glucose and carageenan gum, a love heart embossed on its hard and rippled shell, and inside that heart the words

For this is a sweet that belongs in the rejected pile, yet that somehow escaped the shrewd and narrow eye of the woman who works at the end of the line at the factory, whose job it is to seek out those imperfect hearts and throw them away. It does not occur to her that she is a heart breaker.

TWO

I hold that heart in my hand and I smile because it is corny and because it is silly and because it is flawed and because the man who gives it to me is all of those things too. We have reached the point of our marriage when we look at each other and we each think accommodate. Neither of us uses the word compromise. We are too young and too worldly for that sentiment, which seems to belong to an older time. The word fit my mother like a silk noose. She compromised every day. She complained of her burdens in a quiet way filled with sighs, and the house would hush itself around her to allow her to sit and gather herself, which she did usually in the curved heart of a corner chair, out of sight of my father.

THREE

We accommodate. We allow the little things to come in. He has a smile that is crooked and that dimples his cheeks. It used to make him impish. Now it only makes him look cross. The dimple is a heart-shaped crevice in his cheek, and when he smiles it blossoms like a poison flower. I have dimples too, but they are in my behind. He likes to tickle there because he thinks it is erotic and playful. I saw his face in the bathroom mirror when he stood behind my naked body and first saw them. He said nothing, but I knew how disappointed he was, how those little puckers upset him, and I saw what he saw: the slow creep of age. I saw how he carefully looked at the rest of my body and how he was inspecting it for lines and sags and bulges and spots.

FOUR

Darling, honey, sweetie, babe, sweetheart, love, ducky, snookums, baby, dearest, dear, my heart’s desire, my heart’s true love, light of my life, fire of my loins, sugar, precious, pet, mistress, my Lady, my Liege, my Lord, Sir-Knight, angel.

FIVE

When we first met I made a list of his habits, good and bad. The good outnumbered

the bad two to one. Now the bad outnumber the good four to one. He doesn’t make

lists. He surveys and notices and clucks his tongue when something bothers him, but

he does this quietly, or he used to anyway.

We are clever about love in our own way. We did not fall head over heels or at first sight. Our hearts did not melt. We grew into each other. We grew into what we wanted to be for each other and we grew into what the other wanted each of us to be.

SIX

There is a famous tree in the west of Ireland that young and old lovers would wound with their names, scraping and gouging initials and expressions of desire into its rough bark. If you look closely, you’ll see the initials of a famous poet below a rough heart. He was far gone for a woman but she didn’t think of him that way. He asked her to marry him. She refused. So he asked her daughter instead.

SEVEN

We are bookish types, he and I. You have met people like us before, at dinner parties or at art openings or at first nights or after hours in a nightclub where grown-ups go to talk aloud and pretend to listen to jazz. We have opinions on what was printed in the book review last Sunday and what we heard on the radio this morning and what we are reading right now.

Because we are bookish there is a great book migration that takes place in our house. While books are being read, they are moved around from room to room until they reach their final destination on the shelves that line the hallway by the front door, where they will remain until he decides we need to clear some space, and then there is a culling for the charity shop.

Because we are bookish we have little piles of things to read on each side of the bed. Sometimes – the occasional weeks when we make love more than once – the piles of books are tall and untouched. Right now the pile on my side is low, and because I am a note-taker the books in it are dog-eared and have sticky notes at various points, and soon these books will make their heartbreaking journey to the shelves in the hallway.

EIGHT

God, He knows a little about love, allegedly. He sent His only son to earth to be sacrificed because He loves us. Think about that. It is a reversal of what savages used to do when they ripped out the hearts of virgins to please a volcano. God sent His son for us to kill so we wouldn’t be angry at Him.

NINE

The pile of books by his side of the bed is tall, and getting taller. He is bringing home new books daily but leaving them unread. They are not the kind of books he used to read. He used to read love poetry and long novels about heartache. These all concern wars, real and fictional. The books about real wars have maps of battles and photographs of stern generals and weary soldiers. The books about fictional wars feature men with simple and masculine first names like Matt and Jack and Chuck, who have last names like Strong and Powers and Stone, who brutally fight and kill men with odd and long and unpronounceable names.

He is not reading any of these books because most nights he is asleep within minutes of getting into bed. He is not working longer hours than before or doing more exercise or eating more sweets that spike his blood sugar and then cause him to crash, and because I am a note-taker I listen to his snoring and look at his pile of unread violent books, and I cannot do anything except think he’s tired all the time because he’s screwing someone else.

TEN

I ♥ YOU

ELEVEN

God told Abraham to kill his only son, Isaac. This is the kind of thing that lovers ask of each other daily. Abraham climbed that mountain and built an altar and bound his son and unsheathed his knife and placed it over Isaac’s heart. When we read this tale we wonder did Abraham hesitate even for an instant, and if he did, was it because of what he saw in Isaac’s eyes or what he saw in himself?

TWELVE

We are bookish people, and I am reading A History of Love Poetry. I have to wade through an awful heap of beseech thees and wouldst thous and breasts like jewels and eyes like diamonds and necks as graceful as a swan’s until I can find a truly good verse. This one, for instance:

Set me as a seal upon thine heart,

as a seal upon thine arm:

for love is strong as death;

jealousy is cruel as the grave:

the coals thereof are coals of fire,

which hath a most vehement flame.

And I wonder is that true? I look at him beside me. The heart shaped dimple is winking at me because his crooked smile has crossed his face while he sleeps, and I have to think he’s dreaming of her.

THIRTEEN

I once read a novel about a man who waited too long to open his heart. At the moment of embrace with an old lover, just before they pulled apart, when he could feel her hands at the back of his neck and on his shoulder blade, and when he could get the frail scent of rose in her hair and touch the softness of her cheek and could, if allowed, taste the little heart-shaped curves of her ear, he said “I love you” in a level voice.

He could have said nothing, could have let the embrace continue in silence. Perhaps that peace between the two of them would have led to a kiss. As it happened, he said something, and the embrace ended, and she looked at him with a terrible pity, and she said “I know” and turned and walked through the door marked Departures.

FOURTEEN

Because we are bookish and clever and worldly, and because I am not my mother, we will bypass this little pang in our hearts. We will accommodate it. Or we won’t. There will be no tears or throwing of crockery. He will move into the spare room for a bit. There will have to be an early book migration to allow for this, as the spare room is piled with volumes half-read and to be read. He will bring his war books in there, and maybe they will remain unread there also.

FIFTEEN

Abraham would have killed Isaac if God had not stayed his hand. And the questions you need to ask are:

Was Abraham’s obedience to God greater than his love for his son? Was God moved more by Abraham’s faith or by Isaac’s fear? Did God treat this as a dress rehearsal for the heartache he planned for His own son?

SIXTEEN

We will be disgustingly civil with each other. We are both agreeable sorts and you can still invite us to dinner without fear of a scene, unless that is what you want, in which case we are happy to perform. No shouting, though. We’re not shouting types. He’ll get drunk and surly and I’ll be a withering, cold-hearted harridan, and as our hosts you can squirm in exquisite embarrassment, and after we’re gone you can drink another bottle of wine together and roll your eyes and say “How ghastly she is,” and “Oh, God, I can’t believe he said that,” and then you can go to your own bookish bedrooms and tipsily, smugly fuck each other.

SEVENTEEN

I feel sorry for the Devil. He had his heart broken. God threw him over for us. I wonder does God ever want to get back together with him?

EIGHTEEN

We sit with the lawyer and bookishly exchange banter about how agreeable and accommodating we are. We share her because we’re getting a cooperative divorce. We sign our names and he smiles and the little poison heart on his cheek blinks.

NINETEEN

We have a last lunch together. I pull out my heart from my purse and show it to him.

Afterwards we stand in the street and briefly hug and cheek-kiss goodbye, and my only thought is will he bring Matt and Jack and Chuck and all their bone-cracking ways to her bed?